Below are the stories of the amazing Rwandan's we met along the way...

The word in bold that begins each story (happiness, forgiveness, etc...) is the word that our new Rwandan friends responded to upon receiving their letters.

Written by Steph Fellows

happiness

Alphonse + Trephene

Alphonse has owned four acres of lakefront property in Kamembe for three years and is a contractor

by trade. He waited on developing the land and, lucky for us, people kept visiting, so he was forced

to finish a few cottages for guests. Alphonse joined us over breakfast and eagerly opened a letter

presenting the word “happiness.” The writer had just lost her father-in-law a week before and

expressed the difficulty in encouraging her three daughters to celebrate their Pop Pop’s life. Like

many who have been faced with this situation, it’s easier to recognize the need for happiness than

actually find it.

Happiness is the prevailing emotion in Rwanda. Alphonse was quick to share that the happiest day

of his life was the day he married his wife … until his eldest son got married. Then he truly knew

what happiness meant. He knows that there is only one day that will beat all the rest. It will be the

day his youngest daughter, 21-year-old Trephene, gets married.

Trephene is adopted. During the genocide, her parents used to hide her at Alphonse’s house while

they fled to safety in the mosquito-laden woods. With every sunset, Trephene’s parents would drop

her off, picking her up when the sun returned the following day. Alphonse knew the day would come

when they would not return to pick her up. He promised Trephene’s parents that if this were to

happen, he would love their child as his own. The tears in his eyes spoke much louder than anything

he could say.

Doing the right thing at a time when so many people were doing the wrong thing speaks highly of

Alphonse. It is obvious that he is very successful. He owns houses all over Rwanda, his Lexus has rap

video-worthy rims, and he’s trucking sand onto the shores of Lake Kivu to make a real “beach.” If you

were to talk to him, he’s just like everyone else we’ve met here: humble, soft-hearted and, most of

all, admirable. If you ask him how he is rich, his answer would be about his family and not about his

bank account.

I excused myself from the conversation after breakfast to catch up on some writing and take in the

beautiful views. As I sat in the sun overlooking the lake, a young girl walked over and pulled up a

chair right next to me. She extended a hand and said, “Hello, my name is Trephene.”

At that moment, time stopped. I went over and over in my head the conversation we had just

finished, making sure I had gotten the name right. I was completely overwhelmed and felt

superanxious, because I knew something Trephene didn’t. I knew a secret that will always remain

a secret. I knew that she was an orphan and she didn’t.

As we talked, my mind vacillated between imagining her as a baby and who she is now: a bored

and privileged 21 year-old. Unlike most Rwandans her age, Trephene has little worries. She went to

the best schools, has never gone a day without adequate food or water, and working is not a matter

of survival. Truthfully, it was like talking to an American college student who wants to be with their

friends and go out all the time. She is a happy, healthy young adult who has a bright future and all

the means to accomplish her goals.

Trephene became our official guide for the day, even accompanying us to a primary school. It wasn’t

until the end of the evening, when we had spoken in front of four classrooms, been drenched by

rain, coated in mud and driven in the mayor’s Mercedes, that we said goodbye. She pulled me aside

and said, “Goodbye, Stephania. Thank you for the day. I have learned so much new today. Much

vocabulary and lots of character. Please make sure to tell Morris how much I thank you.”

As we walked away, our guide, Ronald, shared with us that he had invited Trephene to come for a

drink with us. She had declined, saying she missed her dad. She wanted to go home and make her

dad a meal because she knew it would make him happy. If she only knew.

joy

Marcel

All good things start with peanut butter, and the day was still young as we broke out our last jar

for breakfast. Mid-smack, two men walked up looking straight out of a decade long past. One was

ridiculously tall and the other unreasonably short. Both had well-worn walking sticks, blazers and

top hats.

The men walked directly up to our party, started introducing themselves, and we invited ourselves to

their house. As we walked through fields of maize, I learned both men had moved to this region only

two months ago. Their homes were destroyed in a flood and the government had built a little village

called Divisio for all those affected. Walking behind these men made you feel wiser, and as the rain

started to fall, our saunter turned into more of a hop, dodging puddles and one silly photographer

keeping us from being dry.

Marcel, the taller and elder brother, sat across the table, his legs so long that his knees almost

reached the same height as his shoulders. We talked of floods, long walks (he’s walked Rwanda three

times) and the government. His demeanor was grandfatherly, patient and captivating.

After breaking the seal on his letter, I took it in my hands, noting that the topic was “joyful,” and

scanned the sentences until my eyes fell on the word “flood.” My heart sank. My eyes welled up. I

asked Ronald if we should proceed and, also in shock, he said, “Yes.”

How could this have happened? Out of all the letters, how could it randomly be this one? As tears

streamed down my face, my eyes didn’t leave the paper once. I didn’t need to see Marcel’s eyes. I

could feel them.

The letter conveyed a time when the anonymous author encountered a hurricane while living in

Florida. After the clouds parted and the rains subsided, she and her daughter put on rain boots and

went splashing through the puddles. This memory, though preceded by much devastation, illustrates

the importance of finding and holding onto joyful moments in our lives.

The author states she used to think that joy came from big events but now realizes, “It comes from

something else, and we need to look at the simple things that bring joyful feelings to our hearts.”

When there were no words left in the letter, silence fell upon us. The room began to spin, but we

were totally still, grounded to the heart of a man in the middle of it all. Joyful. We were all about to

learn what it meant.

Here was a man starting from nothing again at the age of 60. Joyfulness isn’t just for times of

celebration. It’s a daily practice. Every day, Marcel is filled with joy just to be alive. He says surviving

times of war and the many hardships of past days has made him grateful.

Marcel has three grandchildren and encourages them to be joyful by adhering to three rules: 1) Be

God-fearing; 2) Respect people for who they are; and 3) If they are ever unhappy, he wants them to

come and talk to him. In his words, “I want to teach them to be joy finders.”

This insight wasn’t enough. He wasn’t always going to be there to call upon when it was hard to

be a joy finder. I asked how could I live a joy-filled life. Marcel leaned in close, looked straight in

my eyes and spoke to me directly. (This is a powerful and intimidating thing when you are actually

communicating through a translator.) It didn’t really matter what his words were. This time, instead of

speaking his heart, he was speaking right to mine.

“Live a life guided by the spirit of respect, loving one another because it’s the source of joy. If you

love someone, you will respect them and through these two things the world will find peace.”

Marcel lives in poverty. He had no material gift that would accompany us to our next destination, yet

he made sure to give us one thing as we left: peace, which he assured us is the richest gift of all.

When was the last time you started your day with peanut butter?

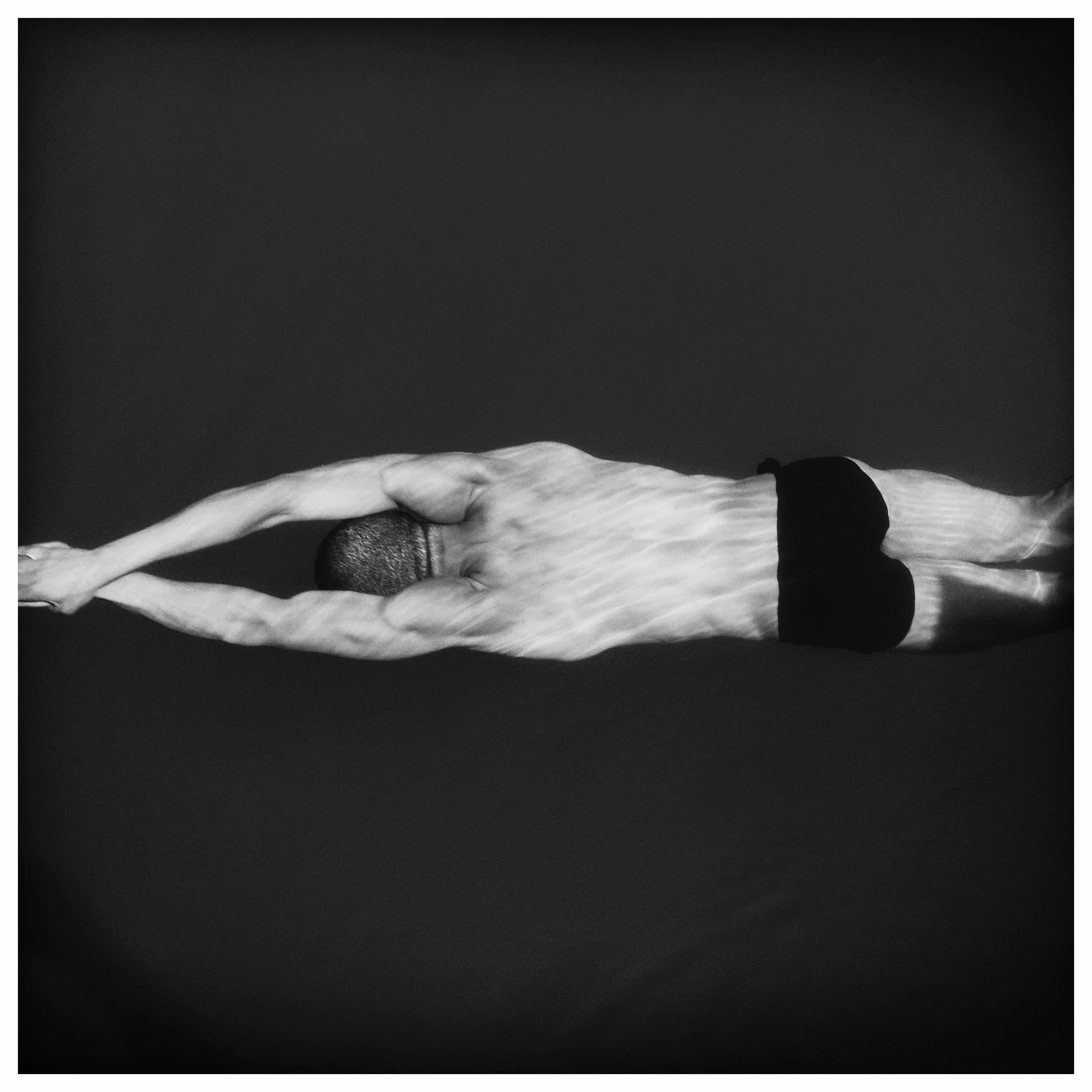

hope

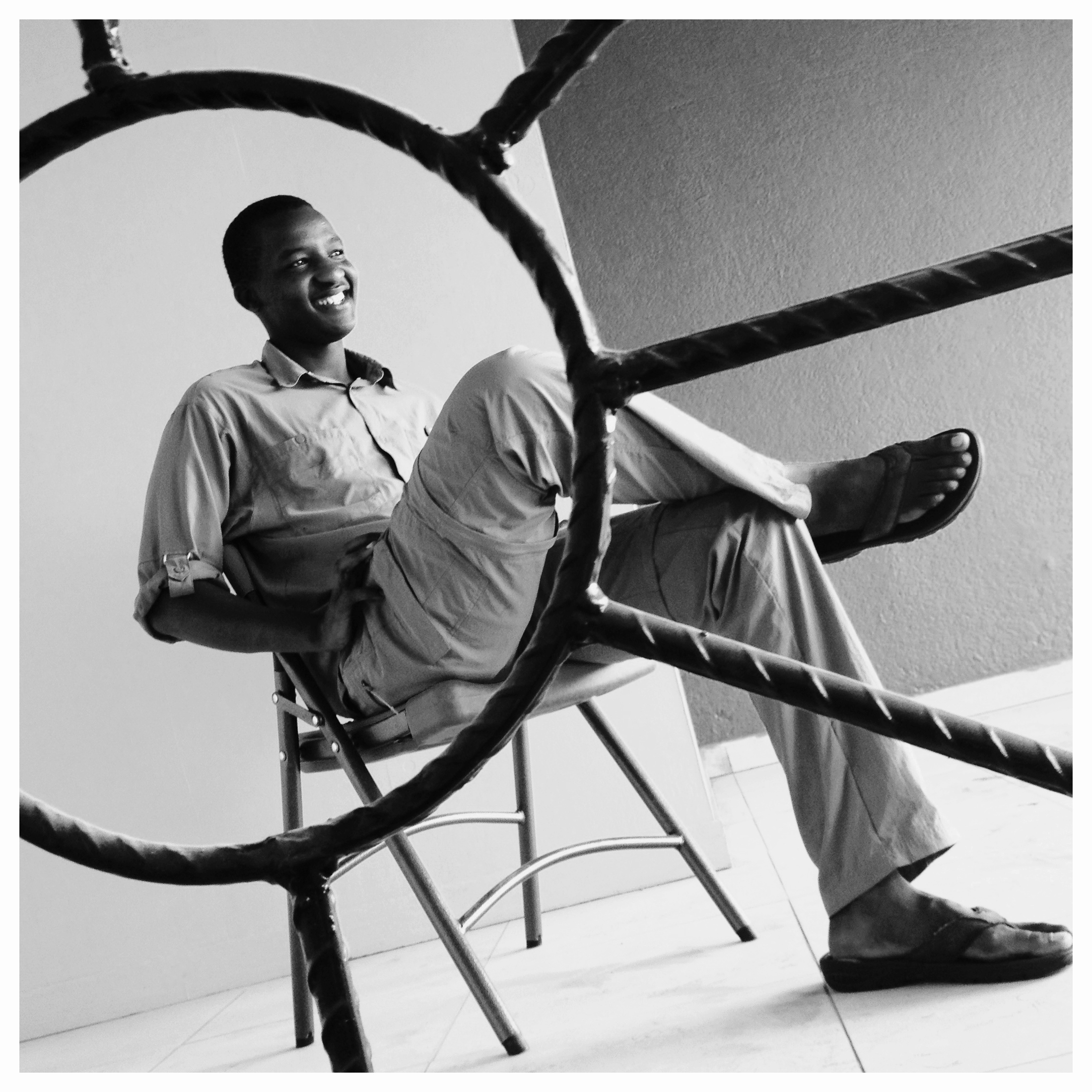

Jackson

Walking down to the water in Kibuye, we found a young man swimming with serious intention. His

name was Jackson, and it just so happened that we needed a boat taxi and he had a boat. As we

talked about the fare for the trip, our future captain mentioned that he was hoping to compete at the

London Olympics. We laughed, thinking it was a joke.

As we boarded the boat, Ronald found out that Jackson was serious about swimming at the 2012

Summer Olympics. This raised some obvious questions; most importantly, if he wanted to go to

London, why wasn’t he there already?

“Trials are tomorrow,” Jackson said.

Here is a kid whose biggest race in four years is tomorrow and he’s sitting in the sun, driving us

around. Interesting training strategy. Jackson would be vying for one of two 50 freestyle spots on

the Rwandan National Swim Team the following morning in Kigali, a four-hour bus ride away. Still

speechless, we kept prying for more answers. The more we found out, the more we felt guilty for

being the reason he wasn’t resting.

Jackson had never had a formal lesson and just started taking swimming seriously when he turned

18 (he’s now 24). As the boat drifted toward shore, Jackson abandoned the motor and joined

us in conversation at the bow of the boat. Asking questions about his training schedule and the

availability of coaches in Rwanda was easy, but being prepared for his answers was not. Jackson

looked at us without blinking and said, “I don’t have time for training if I have to find food too.”

Definitely not a common problem among Olympians. It became apparent that the lack of programs

in Rwanda makes it difficult, if not impossible, to be an international competitor. There is one

coach in Kigali but he’d have to pay all of the associated transport and fees.

Even with all this against him, Jackson has never thought about being anything but a swimmer.

He loves swimming so much that it drives everything he does. He has the hardware to show for his

dedication, too.

Jackson has won 11 medals in his career. Each time the Rwandan flag flies high and the national

anthem plays, he describes the pride he feels as “addicting” and that feeling motivates him to win

every time his toes edge up to a starting block. When we finally got around to reading the letter, it

contained two poems by Joshua Rempel, one titled “Hope” and the other titled “Satisfied.”

Morris chose to read the poem “Hope” with these appropriate lines:

Summer comes for us all

maybe not every day

sometimes not even every year

but when the orchard in your head

reaches full bloom

Jackson’s summer is now. And he described his trials race as the equivalent of a ticket for a bus

ride into the future. In order to proceed to the upcoming Olympics, Jackson needs to win his trials

heat. There are two competitors he sees as threats to victory, and they have training and nutrition

on their side. Even with absurd statements like this, Jackson leads every thought off with a chuckle

and finishes with a smile—which makes it believable when he said that if he doesn’t win tomorrow,

there will always be more races, more chances.

After our talk, Jackson went to the stern of the boat. Apparently, he turned to Ronald and admitted

to being anxious about the race, but after talking with us he said he felt like he’d already won.

The second poem was titled “Satisfied.” This was an equally eloquent poem but very hard to

translate, so it did not fall on Jackson’s ears. I have to believe that the last line was meant for him

when it said, “the splendor in an ending that was never left to fate.”

If you by chance watched the Opening Ceremonies, you would’ve seen Jackson leading the way into

London’s Olympic Stadium.

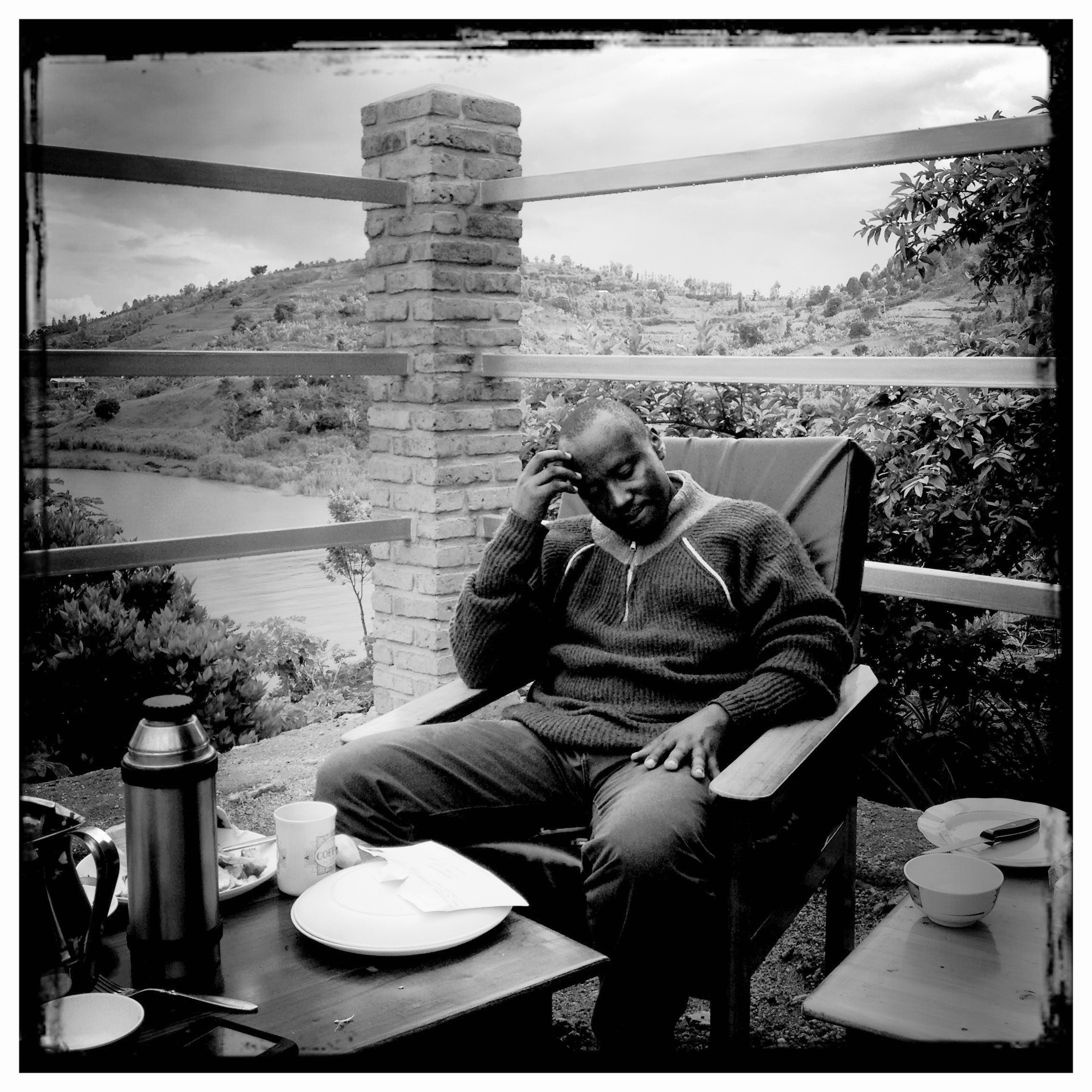

forgiveness

Gervais

Much like the chalet system in the French and Swiss Alps, the Congo Nile Trail has guest houses

found along its route every few days. These houses have showers, beds, laundry and the most

wonderful staff. The Kinunu house is 10 feet away from a coffee bean-washing station with mango,

papaya, guava and banana trees leading you down to the shores of Lake Kivu. The manager of the

coffee station, and house, is a smart, ambitious Rwandan who totally captured our attention, not for

one but two days.

Gervais is 34, married and has two kids. It’s important to note that Gervais is different than many of

the Rwandans we met. He’s very at ease with us, smiling and making jokes. He also asks questions.

You’d think that this is a result of quality education but instead of going to secondary school, he was

a refugee in the Congo waiting out the war. This is how we found out that Gervais is the only one in

his family still alive.

As the sun warmed up the fruit-laden hills, our perceptions of what coffee should taste like was

changed forever. Gervais’ coffee is ranked eighth-best out of 250 in Rwanda and it was over the fruit

of all his labor that he agreed to receive a letter titled “forgiveness.”

Forgiveness is not something that comes easily every day to Gervais, but he makes the choice

to forgive in order to move forward. The Kinyarwandan word he used for forgiveness means

“foundation”; it is what he has built his life around. Two of the men who killed Gervais’ family

work for him. Not only do they work for him but Gervais hired them himself. At the very moment

he was sharing this, one of them walked by with a load of dried banana trunks on his head.

Gervais sat smiling.

This level of reconciliation is unfathomable. His rationale is if the men remain distant, they will

remain enemies. This lack of communication and contact will lead to shame and guilt for what they

have done. If Gervais refused to forgive, he would not experience freedom on a daily basis and would

live a life devoid of community. And a life without community is not a Rwandan life.

When asked if it is harder to hold a grudge or forgive, he replies, “It depends on what they did. It is

something I struggle with even when I am sleeping. Forgiving is like a wound that’s healed but you

still have the scar. But by forgiving, I am able to live free and have a free heart.”

How do you forgive someone who doesn’t ask?

“It is harder for them to ask for forgiveness than it is for you to forgive them. They will ask, ‘How do

I go in front of this person with all I did?’ Remember when you wronged your parents and you didn’t

even want them to look at you? So, it’s better for you to show these people that you can have coffee

and make them feel free to get closure.”

Gervais believes that his dreams are coming true as a result of his practice of forgiveness. In

essence, the freedom that he chooses every day, and that he extends to those who are undeserving,

has opened up opportunities that should not have been offered to him.

Call it karma. Call it a reward. There’s no denying that this man is changing the world. I hope that

every time you take a sip of coffee, you take in a little bit of Gervais’ spirit, because if there’s one

thing that he is more passionate about than coffee, it’s forgiveness.

patience

Theresa

“What makes a good life?”

At different times and in different parts of the world, the answer to this question varies. Africa

teaches that a good life is simple. And a simple life is good. Our letter from the one and only Mrs.

Martha Morris, Morris’ mother, corroborated this teaching.

After a healthy portion of goat heart, Theresa Nyirabangaizi and her son were spotted in their garden,

nostrils glowing with golden earth. Seeking privacy from the ever-growing crowd, we retreated to

Theresa’s house on the back of her property. It was here that the boisterous and taunting demeanor

Theresa displayed while in the garden became reserved. Upon receiving the letter, a light crept

across her weathered face. In that moment that she no longer looked like an adult, but returned to a

child. It never gets old seeing delight like that.

“I admire you very much,” Martha wrote. “I admire you because you exercise much patience in your

life and that is a quality that is important for a good life and strong relationships. You have been

patient all of your life, for basic things like water to drink and food to eat.”

With these words, Theresa succumbed to fatigue. You could see it on her face and in her body

language. It’s as if someone had just told her, “Yes, I know you’ve been working hard for a long time

and now it’s OK if you admit to being tired.” She has five kids, a house that does not stand a chance

against monsoon season and is in charge of most of the farm work throughout the year. Patience is

evident in all that she does.

“I believe patience is one of the nine most important qualities to have. To me, the most important

qualities are peace, patience, love, joy, kindness, goodness, gentleness, faithfulness and selfcontrol.

I could’ve written about any of these, but I chose patience because I think your life requires

great patience,” Martha wrote.

Theresa agrees that these are important but offered up just three: joy, patience and love. I asked

Theresa if she could recall a time that waiting patiently was unbearable. With slight timidity, her

response was concise: in times of war. The only thing that kept her going was faith that peace was

coming and the many lives lost would not continue to grow.

“ … and patience produces peace, joy, strength of character and self-control.”

The above statement is a description of every African I’ve met. Peace in the present. Joy in the little

things. Strength of character from hard work. And self-control from community-mindedness.

“With these five qualities you have a good life,” Martha wrote.

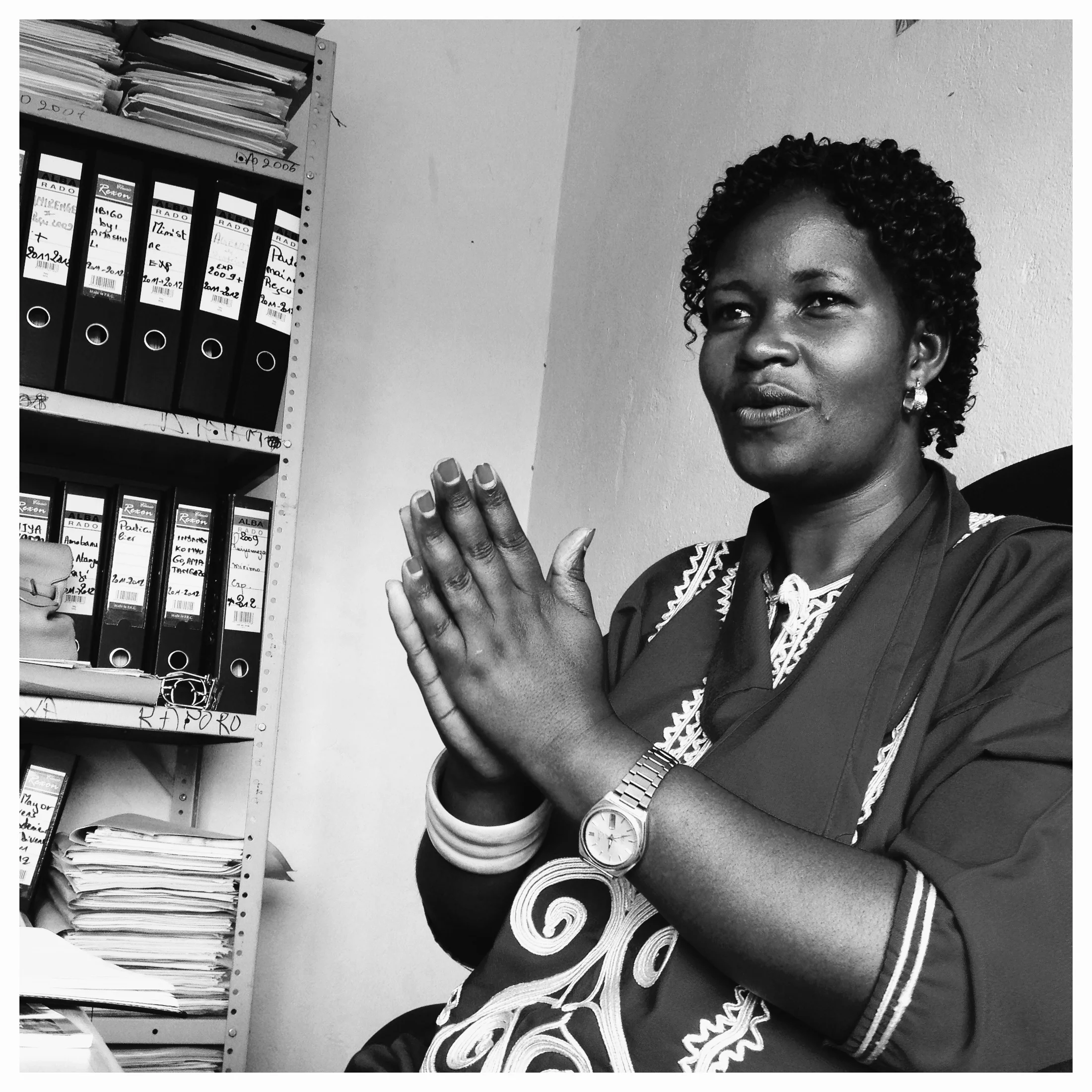

proud

Catherine

Catherine is the vice mayor of the district of Nyamasheke. She is a large woman by Rwandan

standards and has some serious jerry-curled hair. She was wearing a beautiful, green two-piece

outfit embroidered with gold trim when we met her in the district office. As Catherine became more

animated, the bangles and rings adorning her hands clinked and clanked. Catherine is a widower

and lost her husband when the youngest of her four children was only 1 year old. She completed

college with a degree in community development just before her husband passed away.

While praising the Rwandan people for the hospitality and national pride we encountered along

the trail, Catherine challenged us to find another African nation as unified as Rwanda. Obviously,

Rwanda is different than many African nations and the catalyst for these prosperous times is

President Paul Kagame. According to Catherine, Mr. Kagame is a “gift from God.” Of his many

accomplishments, Mr. Kagame will always be remembered for unifying Rwanda after those terrible

100 days in 1994. “Rwandans love the government because the government loves them,” she

said. Mr. Kagame is the reason why Catherine wholeheartedly can speak these words. He did the

unthinkable and continues to inspire his people.

Most of Catherine’s week is spent in the field with many in her district. “Our people are poor. It is

our obligation to love them,” she said. “To help them grow out of poverty, we must work together. We

must discuss our culture with them because our culture doesn’t work hard. To change that, we must

work hard with them.”

Her office looks out to Lake Kivu and across to the shores of the Democratic Republic of Congo. It

was on those shores not too long ago that tents of all different colors, each displaying a different

acronym, permanently stared back. UN, UNICEF, WHO and many others were the bridge to safety

for refugees. In Catherine’s mind, the greatest sign of progress over the last 15 years is that the

occupants of those hills are now cows. And this makes Catherine proud. Proud of her people. Proud

of her government. And proud to be an agent of change for the future.

connected

Ronald Mugisha

Ronald is 21 and an aspiring tourism expert. He was not just our translator, but a brother. Ronald

endured rain, days consisting solely of bread for calories, showerless mornings, the requests of two

crazy “muzungus,” uncomfortable stares from his own people, his first blister and pages upon pages

of experiences that will forever change all of our lives.

He is the second of four children ranging from 5 to 26. A little over five years ago, Ronald lost both

of his parents within months of one another to AIDS. At the age of 15, he was in charge of taking

care of his two younger sisters, a role that he lovingly and dutifully fulfills to this day.

As with all untreated carriers of HIV/AIDS, the condition of Ronald’s parents worsened quickly. They

could no longer hold jobs, and providing for the family became an issue. Ronald’s wage went to the

household’s needs from the very beginning. With money in his pocket and two parents bedridden,

Ronald decided to make a stop on his way home one day. As he entered his house he went straight

to his parents’ sides, placing two Bells (Ugandan beers) in front of his father’s ailing body and a bag

of groceries in front of his mother. His mother’s reaction was solemn, leading him to think that she

was angry. Moments passed, and her face remained unchanged. Just as Ronald became worried, his

mother’s eyes filled with tears. For all the times that she had taken care of him, it was now his turn

to care for her.

A self-proclaimed “momma’s boy,” within an hour of being in his company, you understand that

the connection they had shaped him in every way. Often, Ronald’s mother would tell him that he

needed to learn how to cook because one day she wouldn’t be there. She passed on parables like,

“Do everything with a profit in mind, because what is work if you don’t have anything to show

for it.” Ronald was not by his mother’s side as she took her last breaths, but even in these last

moments, her final words were a cry for him. Their connection is one that cannot be broken. Not

even by death.

Among a myriad of postcards, pictures and words, Benjamin Carlson had one simple question for

Ronald: “I am overwhelmed and excited to know just one thing about your day. When you woke up

today, what did you aim to do with your time? And how did the progression of your day lead you to

be connected with my friends delivering this letter?”

Every single fiber of the connection that binds me, Ronald and Morris was hard-earned. We are

united. We are a family. And the one word that describes our story is “connected.”